Back Spaanse Ryk Afrikaans الإمبراطورية الإسبانية Arabic الامبراطوريه الاسپانيه ARZ Imperiu Español AST İspaniya imperiyası Azerbaijani ایسپانیا ایمپیراتورلوغو AZB Imperyong Espanyol BCL Іспанская імперыя Byelorussian Испанска империя Bulgarian Impalaeriezh trevadennel Spagn Breton

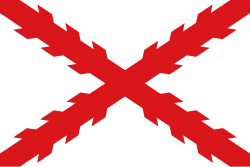

The Spanish Empire,[b] sometimes referred to as the Hispanic Monarchy[c] or the Catholic Monarchy,[d][4][5][6] was a colonial empire that existed between 1492 and 1976.[7][8] In conjunction with the Portuguese Empire, it ushered in the European Age of Discovery. It achieved a global scale,[9] controlling vast portions of the Americas, Africa, various islands in Asia and Oceania, as well as territory in other parts of Europe.[10] It was one of the most powerful empires of the early modern period, becoming known as "the empire on which the sun never sets".[11] At its greatest extent in the late 1700s and early 1800s, the Spanish Empire covered 13.7 million square kilometres (5.3 million square miles), making it one of the largest empires in history.[3]

Beginning with the 1492 arrival of Christopher Columbus and continuing for over three centuries, the Spanish Empire would expand across the Caribbean Islands, half of South America, most of Central America and much of North America. In the beginning, Portugal was the only serious threat to Spanish hegemony in the New World. To end the threat of Portuguese expansion, Spain conquered Portugal and the Azores Islands from 1580 to 1582 during the War of the Portuguese Succession, resulting in the establishment of the Iberian Union, a forced union between the two crowns that lasted until 1640 when Portugal regained its independence from Spain. In 1700, Philip V became king of Spain after the death of Charles II, the last Habsburg monarch of Spain, who died without an heir.

The Magellan-Elcano circumnavigation—the first circumnavigation of the Earth—laid the foundation for Spain's Pacific empire and for Spanish control over the East Indies. The influx of gold and silver from the mines in Zacatecas and Guanajuato in Mexico and Potosí in Bolivia enriched the Spanish crown and financed military endeavors and territorial expansion. Spain was largely able to defend its territories in the Americas, with the Dutch, English, and French taking only small Caribbean islands and outposts, using them to engage in contraband trade with the Spanish populace in the Indies. Another crucial element of the empire's expansion was the financial support provided by Genoese bankers, who financed royal expeditions and military campaigns.[12]

The Bourbon monarchy implemented reforms like the Nueva Planta decrees, which centralized power and abolished regional privileges. Economic policies promoted trade with the colonies, enhancing Spanish influence in the Americas. Socially, tensions emerged between the ruling elite and the rising bourgeoisie, as well as divisions between peninsular Spaniards and Creoles in the Americas.[13] These factors ultimately set the stage for the independence movements that began in the early 19th century, leading to the gradual disintegration of Spanish colonial authority.[14] By the mid-1820s, Spain had lost its territories in Mexico, Central America, and South America. By 1900, it had also lost Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippine Islands, and Guam in the Mariana Islands following the Spanish–American War.[15]

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

- ^ Monarchy nominally restored in 1947

- ^ Government proclaimed in 1936

- ^ a b Taagepera, Rein (September 1997). "Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia" (PDF). International Studies Quarterly. 41 (3): 492–502. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00053. JSTOR 2600793. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 July 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ Fernández Álvarez, Manuel (1979). España y los españoles en los tiempos modernos (in Spanish). University of Salamanca. p. 128.

- ^ Schneider, Reinhold, 'El Rey de Dios', Belacqva (2002)

- ^ Hugh Thomas, 'World Without End: The Global Empire of Philip II', Penguin; first edition (2015)

- ^ Wright, Edmund, ed. (2015). A Dictionary of World History (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780192807007.001.0001. ISBN 978-0191726927.

- ^ Echávez-Solano, Nelsy; Dworkin y Méndez, Kenya C., eds. (2007). Spanish and Empire. Nashville, Tenn.: Vanderbilt University Press. pp. xi–xvi. doi:10.2307/j.ctv16755vb.3. ISBN 978-0826515667. S2CID 242814420.

- ^ Beaule, Christine; Douglass, John G., eds. (2020). The Global Spanish Empire: Five Hundred Years of Place Making and Pluralism. Amerind Studies in Anthropology. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. pp. 3–15. doi:10.2307/j.ctv105bb41. ISBN 978-0816545711. JSTOR j.ctv105bb41. S2CID 241500499. Archived from the original on 30 August 2021. Retrieved 6 August 2021 – via Open Research Library.

- ^ Gibson 1966, p. 91; Lockhart & Schwartz 1983, p. 19.

- ^ Márquez, Carlos E. (2016). "Plus Ultra and the Empire Upon Which the Sun Never Set". In Tarver, H. Micheal; Slape, Emily (eds.). The Spanish Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia [2 volumes]: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 161. ISBN 978-1610694223. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ Kamen 2003, p. 69.

- ^ Kamen 2003, p. 506.

- ^ Lynch, John. "Spanish American Independence" in The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Latin America and the Caribbean 2nd edition. New York: Cambridge University Press 1992, p. 218.

- ^ Scheina 2003, p. 424.